The Liberation of Bangladesh: India's Finest Military Hour

Fifty-four years ago, on December 4th, 1971, the Indian Armed Forces embarked on a military campaign that would reshape Indian-subcontinent history and give birth to a new nation. The liberation of Bangladesh stands as a defining moment when a young democracy demonstrated both moral courage and military prowess in the face of genocide and humanitarian catastrophe.

An Ancient Civilisation Breaks Free

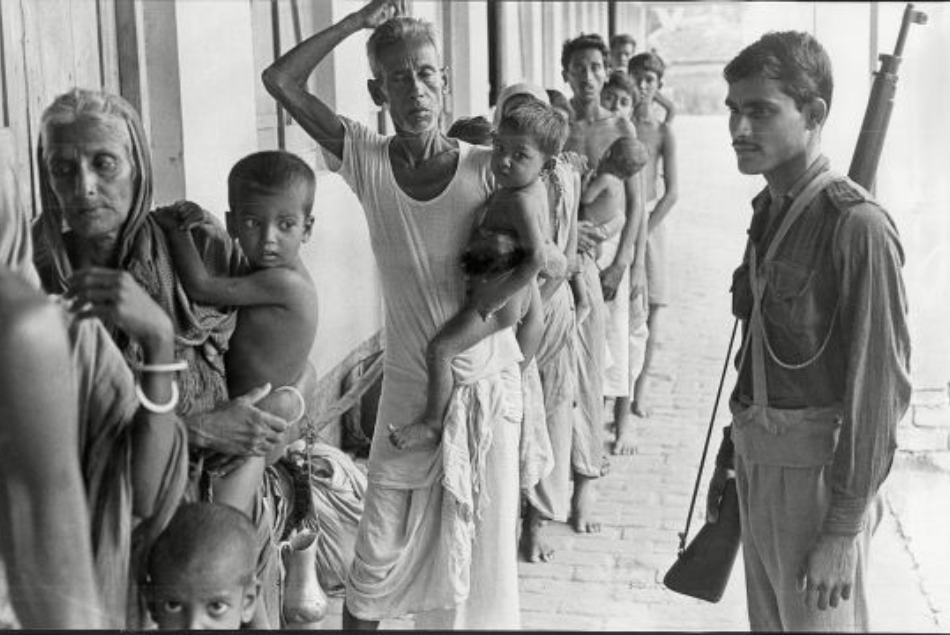

The liberation war of 1971 was more than a military engagement; it was a civilisational struggle against oppression. As Pakistani forces and Islamist militias conducted a brutal campaign in East Pakistan, displacing millions and murdering an estimated two million people, India faced an impossible choice: remain silent as a humanitarian disaster unfolded at its doorstep, or intervene despite international pressure and the implicit backing Pakistan enjoyed from global superpowers.

India chose intervention. The nation absorbed nearly three million refugees regardless of their faith, providing shelter, sustenance, and hope to those fleeing genocidal violence. This act of humanitarian generosity, undertaken by a newly independent country still finding its feet economically, demonstrated the values that would define India’s approach to regional stability.

December 4th: Indian Navy Strikes

December 4th is commemorated as Indian Navy Day, marking one of the war’s most decisive operations. On this day in 1971, Indian navy’s missile boats struck Pakistan’s naval installations at Karachi with devastating effect. The operation saw the destruction of key vessels and extensive damage to Pakistan’s western naval capabilities, demonstrating India’s command of the maritime domain. This was only the second time after the Second World War (after the Egyptian missile boat strike on the ship Eilat 1967) that operations were carried out, but this time the outcome of the conflict would change as the port of Karachi burned. operations were carried out, but this time the outcome of the conflict would change as theport of Karachi burned.

Simultaneously, at Visakhapatnam on the Bay of Bengal, the Indian Navy achieved another strategic victory with the sinking of the PNS Ghazi, a Pakistani submarine that had been prowling Indian waters searching for the INS Vikrant. These coordinated strikes across both naval theatres showcased the operational sophistication and seamless execution of India’s military planning.

The day also witnessed the legendary Battle of Longewala, where Indian forces decimated Pakistani armour in the Rajasthan desert, a defence that would become part of military folklore for the 120 troops of the Alpha Company (Punjab Reg) and few Border guards held off an entire Pakistani Division aided by two Armored Squadrons of 30 tanks of the 22nd Cavalry. This put paid to Ayub Khan’s (later self-appointed ‘Field Marshal’) plan of the ‘’Defence of East Pakistan lies in the West’’.

Battle of Basantar: The defence of Shakargarh plains: 2Lt Arun Khetarpal (17PH)

The ‘’Defender’s Nightmare’’ on the borders of the Punjab plain was the Shakargarh ‘bulge’ as it was lacking canals or boggy fields that were the usual defences/hurdles against rapid tank deployment. Realising this the Pakistanis put up an Armored division led chiefly by the newly inducted American M48 Patton which was billed to wrest victory for Rawalpindi. Standing against this was the British Centurion of the 17 Poona Horse, a regiment which stood rock solid in defence six years ago sacrificing Lt Col Tarapore.

Fighting against huge odds, the fresh academy graduate Lt Khetarpal stood his ground and kept on the offensive even after taking a lethal hit having previously destroyed four tanks.

Even in his last days, 2nd Lt Khetarpal’s guru/mentor and Chief Commanding officer of the 17 Poona Horse, Lt Gen Hanut Singh narrates fondly his memoirs of his favourite student, Arun. It must be remembered that Pakistani Armoured operations command were both wary and in awe of the ‘Father of Indian Armoured Warfare’ Lt Gen Hanut Singh (later awarded the Maha Vir Chakra, the second highest war-time honour).

Meghna Crossing: the maverick Lt Gen Sagat Singh's Masterstroke

While December 4th marked the beginning of hostilities, it was December 9th that saw perhaps the war’s most audacious military manoeuvre. Lieutenant General Sagat Singh, commanding forces in the eastern sector, executed a heliborne crossing of the River Meghna that would accelerate the fall of Dhaka by weeks, if not months.

General Sagat Singh, a true-blooded Rajput officer who had served in the Bikaner State forces before independence and worked his way up through the ranks, made a decision that changed the course of the war. Disregarding the more cautious orders of Eastern Command’s General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, General Jagjit Singh Aurora, Sagat Singh launched his forces across the Meghna in a bold airborne operation.

The gambit succeeded brilliantly. By bypassing Pakistani defensive positions and striking deep into East Pakistan’s heartland, Sagat Singh’s forces unhinged the enemy’s entire defensive strategy. The manoeuvre exemplified the aggressive, decisive leadership that wins wars.

However, military brilliance came at a personal cost. For contravening orders, despite the stunning success of his actions, Sagat Singh was denied promotion and further recognition. His career became a footnote to the very victory he had helped engineer, a reminder that institutional hierarchy sometimes struggles to accommodate the maverick genius that warfare demands but society consigns to the attic of memories

A Democracy's Defining Moment

The 1971 liberation war represented more than military triumph. It was a statement by the world’s largest democracy that it possessed both the will and capability to act decisively in defence of humanitarian principles. India liberated Bangladesh through democratic consensus, with parliamentary support for military intervention, a rarity in a region where military adventurism was typically the province of dictatorships.

Against a nefarious dictatorship in Rawalpindi bent on ethnic annihilation, India demonstrated that democratic nations need not be paralysed by indecision when confronted with genocide. The creation of Bangladesh validated the principle that newer nations could shape their regional environment rather than merely react to it.

Legacy and Remembrance

The liberation of Bangladesh remains a watershed in the history of the Indian subcontinent. In thirteen days of fighting, the Indian Armed Forces achieved what many thought impossible: the creation of a new nation through military intervention. Over 93,000 Pakistani military and paramilitary personnel surrendered, the largest such capitulation since World War II.

For India, December 1971 represents both pride and reflection, pride in military excellence and humanitarian commitment, reflection on heroes like Sagat Singh and Hanut Singh whose contributions were not fully honoured in their time. As we mark fifty-four years since these momentous events, the liberation of Bangladesh endures as a testament to what can be achieved when military prowess serves a moral purpose.